Between Sports and Business – National Esports Associations in Europe

by Miia Siutila*Email: mimasi@utu.fi

Received: 19 Dec 2022 / Published: 04 Jan 2024

Abstract

Aims: This article presents a study focusing on national esports associations in Europe. The study aims at discussing the differences and similarities in the associations approaches to legitimizing and growing the national esports scenes.

Methods and results: Innterviews of representatives from eight national associations from Europe (Austria, Denmark, Finland, France, Macedonia, Netherlands, Sweden and UK) and further contextual interviews with professional players, tournament organisers and esports journalist are analysed and presented. While the national contexts of the associations vary greatly, their aims, goals and immediate actions are very similar in the wider perspectives. The associations mainly differ in two aspects: their approach to commercial esports and on the level of influence they are able to exert on and about the nationals esports scene.

Conclusions: While minutae and details of the associations differ, it is still possible to discern wider commonalities and differences that are not a product of national contextual differences. The article highlights the pattern of increasing influence of commercial actors also on smaller national scenes.

Highlights

- The national esports associations in Europe are very similar in their wider aims, goals, and activities, despite very different national contexts in the relevant legislation and esports scenes.

- The article provides an example of how national developments can be compared despite the varied contexts and details and the accompanying challenges on two vectors: firstly, the level of involvement from commercial esports and, secondly, the level of power of the associations in the esports scene and in the wider society

Introduction

National esports associations are part of the “third sector”: typically, non-profit organisations that are not part of the public sector organised by governments, nor of the profit-driven private sector. In addition, national esports associations are often thought as a counterpart to the various national sports associations that govern, organise, and represent their sports to the wider public, governments, and businesses. In many cases, the national esports associations themselves try to join the national head organisations of traditional sports.

Studying national associations is important, as they are increasingly becoming influential actors in national esports scenes, shaping and influencing the local scenes and (governmental) policy on esports. Currently there are esports associations in nearly every country (IeSF, 2023), but only a fraction of them have been studied. This study focuses on the national esports associations in eight European countries (Austria, Denmark, Finland, France, Macedonia, the Netherlands, Sweden, and the United Kingdom). By interviewing the representatives of these national esports associations in Europe, this research asks: what are the positions of these associations in their own national contexts, whose agenda do they drive, and what are the major struggles they face in achieving their goals?

Literature Review: Local and National Esports

There is very little research on national esports associations, and most are accounts of the development of a single association. Perhaps the most globally recognised and researched national esports association is the Korean Esports Association (KeSPA). Established in 2000, it has been a driving force in the growth, governance, and legitimisation of esports in South Korea. From its very inauguration, KeSPA has had the support of South Korea’s government (Jin, 2010).The association itself is closely interlinked with various stakeholders of the Korean esports scene, including major corporations and the government. (Taylor, 2012; Jin, 2010). It is relatively safe to say that the association has played a major part in the growth of Korean esports into the global powerhouse it is today, especially by managing the relationships among important local stakeholders. Both the support from the government and the involvement of the commercial sector have been integral to its success (Jin 2010).

In their work, Tjønndal and Skauge (2021) focus on the development of esports in Norway. Their analysis begins in 2016, but they note that, before that time, there was resistance from the official sports organisations and the mainstream community to accepting esports as a legitimate sport. In 2016, upper secondary schools began to include esports in their sports programmes, often modelling the esports tracks closely to those of traditional sports. From 2017 onwards, sports clubs have been including esports in their programmes. In both cases, leaders argue that esports provide youth with the same benefits as traditional sports, such as social skills, healthy lifestyles, and fair play. (Tjønndal & Skauge, 2021). Their paper discusses both the association’s influence in Norway and the support it receives from sports and the government.

Vansyngel et al. (2018) studied the institutionalisation and structure of esports in France, stating that esports in France are divided into two, associative (amateur) and professional, that do not really cooperate or even exist in the same spaces. The French esports association aims to bring together the fragmented esports scene and the various actors related to it, from amateur and professional players and teams to tournament organisers and even (esports) game developers. Thus, France Esports describes itself as an association of the whole esports industry and aims to represent all the facets of the industry to the French government and public (Vansyngel et al., 2018) Nevertheless, the French esports scene suffers from lack of funds, as both amateur and professional clubs struggle to make ends meet (De Moor et al., 2022).

Thiborg (2009) conducted the first comparative study on esports associations, focusing on the aims and purposes of national esports bodies based on website analysis. He argues that the national associations aim to govern esports locally, unify the local esports field, and spread information about esports and promote it to the wider audience. While the aim of establishing esports as a sport in the national context was not explicitly declared on all the studied websites of the national associations, he still argues it to be an obvious aim. Thiborg also notes that, while the general aims and goals of the associations are similar, their means of achieving them differ (Thiborg, 2009).

Finally, Witkowski (2022) focuses on problematising the “involvement of nonprofit, public and private sectors under esports modernization . . . addressing diverse adversarial encounters, growth mechanisms and group-based tensions affecting local governance” using four esports associations (Denmark, France, Israel, EASA) as examples (Witkowski, 2022, p. 3). According to her, the esports associations have various motives behind their formation, from profit focusing and economically driven substitution and intervention to a more egalitarian wish to grow, govern, and organise the local scenes. The esports associations of today, however, in Witkowski’s study remain a nascent form of associationalism, with limited obligation or accountability demonstrated for equitable board leadership and performative statements over strategic goals and responsibility to develop national esports as an inclusive platform from the inside out. (Witkowski, 2022, p. 18)

Methods

Data

The research draws primarily from semi-structured interviews (N=8; cf. Kallio et al. 2016) conducted with the representatives of national associations (most often the presidents) and five supporting interviews with other local actors in the esports scenes, such as professional players, tournament organisers, and an esports journalist. The interviewees were selected by convenience sampling: all esports associations that could be found were contacted through email or social media and all that agreed for interview were interviewed. The supporting interviewees were contacted by the recommendation of the national associations as possible sources of further, more detailed and often historical knowledge. The interviews were conducted between summer 2017 and summer 2018 and were, on average, one hour long. Making use of the years since the interviews, I have followed up on the developments on the various scenes by collecting articles, announcements, annual reports, and other data from news sources and the associations’ websites and social media, which parallel the method used to establish the initial findings in this esports domain (Thiborg, 2009). Through this additional data, I have been able to update the developments of the national associations’ current situations, aims, and goals.

The interview questions focused on three major themes: the history of the associations, their current situation and structure and their future plans for themselves and regarding esports in their country generally. The semi-structured interview frame can be found in Appendix 1.

Analysis

The interviews were analysed by a comparative deductive approach. The aims, goals, and missions reported in each interview were first identified. All data were then coded using qualitative content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005) under the four categories preidentified by Witkowski (2022). The four categories are described as follows.

Industry Mode

The industry mode of esports associations is characterised most heavily by the strong influence and inclusion of the esports industry into the decision-making and operations of the association. While other stakeholders, from grassroots to educators, may be involved, it is industry’s interests that are strongly represented (Witkowski, 2022, p. 157). The challenges of this mode stem from the heavy participation of industry, as other voices may remain unheard (Witkowski, 2022, pp. 157–158).

Substitution Mode

In the substitution mode, several parties have set up their own competing association and are trying to use them to forward their interests. In the example used by Witkowski (2022, pp. 159–161), an association was set up in Oceania by an esports industry representative to further their economic interests. Witkowski describes the associations in this instance as “corporatized” (Witkowski, 2022, p. 159), but they could also be created to cater to other parties. The challenges of this mode include questions of legitimacy and influence, as competition among associations diminishes their influence (Witkowski, 2022, p 160).

Early-Adopter Mode

In the fourth mode, the association is set up by a few individuals with personal experience and interests in the esports scene. They are the pioneers who have been involved in the local esports since their very beginning (Witkowski, 2022, pp.161–162). Inclusion in boardrooms and meetings comes from personal relationships and recommendations (Witkowski, 2022, p. 162). Typically, the early-adopter associations are at their beginning and may develop into some other mode in the future. The challenges include a lack of representation and lack of influence and legitimacy (Witkowski, 2022, p. 163).

One of the countries did not include any notable elements from the four categories, and it is thus reported as a separate case study in the results. The aims, goals, and missions were additionally identified from the data of each country for descriptive reporting.

Results

Descriptive overview of associations

Austria - eSport Verband Österreich

The Austrian eSport association was established in 2007 to answer a need for cooperation and organisation among the actors involved in esports. At the time, the association was more active in directly organising competitions and leagues, but now their operations focus more on generally supporting the esports scene: being the point of contact for internal and external stakeholders, helping and educating players, teams, referees, and managers, and creating a clearer structure for getting involved and advancing in esports. The association was also in talks to become a member of the Austrian Federal Sports Organisation and for esports’ becoming “a sport: in Austria, but so far this has not happened.

Denmark – Esport Danmark

The Danish esports association was established by enthusiastic participants of the Danish esports scene. Their aim was to create a more sustainable structure for esports in Denmark, support establishing the grassroots scenes and clubs. and become the voice of esports in Denmark. At the time of the interview in 2017, the association was set up like a typical sports association in Demark and was trying to enter the three sports confederations that govern sports in the country. They felt that, while their influence in the non-professional side of esports was secure, the professional esports teams did not care about the association’s work at all. Now, in 2023, the association has succeeded in entering the sports confederations and cooperates with the professional teams.

Finland – Suomen Elektronisen Urheilun Liitto

The Finnish esports federation was established in 2010 to answer a need for an organisation to coordinate, organise, and promote esports in Finland. The early government consisted of enthusiastic people who had been involved in Finnish esports for several years. Today, the association is part of the Finnish Olympic Committee and works with a variety of governmental and third-sector organisations to promote esports as a safe hobby for all and as a high-level competitive activity.

France – Esports France

Esports France was established in 2016 after esports was recognised by French law to be an entity of its own and not a lottery-type game. The association was created to ensure that the regulation of esports would not fall into the hands of lottery institutions and to be an interlocutor of esports with public institutions. Their aims included ensuring that the voice of esports industry was heard when laws regarding esports were established. The association has since grown into the voice of esports in France, with major influence from all sectors of esports industry and the amateur esports scene.

Netherlands – Nederlandse E-SportBond

The Netherlands esports association was originally set up in 2005 with the aim of creating small esports communities and groups and pitting them against each other in competitions. The association was not successful, however, due to not having enough people. At the time of the interview in 2017, the association was undergoing serious restructuring to be able to better coordinate and structure the scene in the future. Today, they organise national competitions in the Netherlands in various games, but, judging from the activity in their social media, this has only been happening starting in 2023.

North Macedonia - Македонската Еспорт Федерација (Makedonskata Esport Federacia)

The Macedonian esports federation was established in 2009 by 11 people with a background in esports, mostly on the industry side. The aim of the federation was to become the governor of esports in North Macedonia and create awareness and understanding of what esports is. In 2017, they were working towards joining the national sports confederation, which they succeeded in doing in 2022, when esports was recognised as an official sport in North Macedonia (Bojan, 2022). At the same time, the federation has established professional gaming clubs and supported teams in training, coaching, and management.

Sweden – Svenska esports förbundet

The Swedish esports association was established in 2006 with the aim of bringing structure and coherence to the esports scene and becoming an association like those in traditional sports. The association received no support from the commercial side of esports, however, and soon faced competition from another association (ESF – eSports förbundet) that had been set up with similar goals. Furthermore, in 2016, Sverok, a youth organisation, also established an association that claimed to be the representative of esports in Sweden. In late 2021, the Swedish esports association (ESF) invited the other associations and local esports actors, teams, and organisers to a summit to discuss the future of esports in Sweden. The summit resulted in the merger of the two “sports associations” under the name of SESF (Svenska esports förbundet). In 2023, the Swedish Sports Confederation accepted SESF as a full member.

United Kingdom – British Esports Federation

The British esports Federation was established in 2016 by Chester King, who received authorisation to establish a national body for esports from the U.K. government. Before this, his only experience in esports was through his son, an avid gamer. The association at the time did not aim to become a governing body or establish esports as an official sport, but rather focused on esports as a worthwhile and beneficial activity for youth. Their focus is on grassroots esports, which they support through school leagues, helping to establish clubs and advising and providing expertise.

Modes of operation

Notable in the coded modes of operation is the tendency for all associations to be part of more than one mode, as well as to change one’s mode as they grow and evolve.

Two associations in this study were mentioned by Witkowski: Esports Denmark, both as an example of the public mode and as an early adopter, and France Esports, as an example of the industry mode.

Early Adopters

All associations except the United Kingdom and France can be described as both early adopters and one of the other modes. Denmark, Finland, Sweden, Austria, Macedonia, and the Netherlands associations were all established by enthusiastic individuals with a history in esports, often as early organisers of competitions or other events. For example, in Austria the association was established by “league organisers and lan-party organisers” in 2007, in Finland by “five event organisers” in 2010, and in the Netherlands in 2005 by three “big names in esports at that time, tournament organisers and community managers.” In all cases, the people who organised the initial associations were notable people in the local esports ecosystems of the time. While there are several years of difference between the birth of the individual associations, the people who established them were consistently those who had been involved in the national esports scenes from their very early stages. It is also worth noting that, even though the interviewees here talked of “organisers” and “managers,” in practice this meant individual people who were leading volunteers that organised semi-regular events, as otherwise there would have been none. None of them were a part of esports-related businesses.

Only Macedonia and the Netherlands, however, can be described as early adopters today. In Macedonia, despite the association’s otherwise progressing towards its goals, it is mostly the same people and organisations that seem to be involved in running the association. In the Netherlands, the association was “going through major restructuring” during the interview and still seems to be at this same stage, judging from its social media and websites. It had an open call for anyone interested in operating the association, and, while it is not clear who is currently running it, it is likely that they are enthusiastic individuals from the local esports scene.

The other associations (Denmark, Finland, Sweden, Austria) have since grown and developed to a stage that they can no more be described as early adopters. Their boards have gone through several changes and now include people outside of esports organisations as well as individuals with shorter histories in the scene.

Public Mode

The other “early adopters” — Austria, Finland, and Sweden—have since developed in a direction similar to Denmark’s in Witkowski’s (2022) study. In all three associations, members come from various stakeholders and groups in the esports scene, and the associations operations include varied interests and perspectives. In all, the focus is on strengthening the local grassroots esports scene and esports in their respective countries as something in which everyone can participate safely, fairly, and without discrimination.

Their paths to the current situation have been quite distinct, however. For Finland, the association has aimed from the beginning to become a governing body and representative of the whole esports scene in Finland and a full member of the Finnish Olympic Committee. While there have been some hiccoughs along the way, their path towards this goal has been quite linear and straightforward, and currently the Finnish association is as exemplary of the mode as the Danish association in Witkowski’s (2022) study.

In similar way, the Austrian eSport Association has been working towards becoming the representative of Austrian esports scene, but, unlike Finland, it has not really managed to integrate itself into the sports federations and structures. It mostly works with cities and municipalities that see esports as a worthwhile activity to support. Sweden today has also become a representative of esports for the local scene and government alike, but, compared to the other early adopters, its path has been convoluted and complicated, and it was only in 2022 that the three competitive associations managed to merge under the name of the current association. In 2023, it successfully applied to become a member of the Swedish Sports Confederation, thus making esports an “official sport” in Sweden, but it remains to be seen how well the new association will work.

Substitute Mode

Around the time of the interviews in 2017, Sweden had three competing organisations, each aiming to be the national esports association. Two were organised similarly to a sports association, and one was created under Sverok, a youth organisation. All their aims were quite similar, but competition among the three ensured that none had the ability to really be the representative of esports in Sweden. All had problems with legitimacy: ESF and SESF as they had few resources and Sverok as it was seen as an outsider by most of the competitive esports scene. None of the three had much support from commercial esports: professional teams and major tournament organisers like DreamHack “[did] not care what [they did] at all” (personal communication with SESF representative, June 2017). Only after the merger and a clear division of labour has the association managed to truly start to work towards its goals.

Industry Mode

The final mode in Witkowski’s study is not quite as strongly visible in any association but France’s. In France, the industry’s interests are strongly represented in the association through its structure, high representation among the members, and active involvement in its operations. North Macedonia is a hybrid of the public and industry modes, as the association is setting up operations that are commercial in nature (e.g., gaming houses, professional teams) and includes heavy representation from the local esports industry on its board but still mostly operates as a “sports association” and is a member of the national sports confederation. In addition, all the other associations also involve the commercial side of esports to some degree, as professional teams and tournament organisers are also welcome as members and (national) competitions are often licensed to be organised by professional organisers.

Mixed Mode

Finally, there is the United Kingdom, which does not really fit any of the modes. It was established by people outside of the esports scene, thus resembling the substitute mode in Oceania, but there was no competition at the time. Commercial esports interests are heavily represented on its board and as advisors to it (similar to the industry mode), but the operations and aims focus solely on grassroots, esports in schools, and local scenes. Their focus is on the civic and public sides of esports (like in the public mode) despite not being represented on the board.

Analysis

Regardless of the mode that best describes each association, their aims, goals, and concerns are very similar and have not changed significantly from those found by Thiborg (2009). All present themselves as the legitimate representative of esports in their respective countries to the government and the public. They aim to educate and advise various external stakeholders about esports and thus wish to influence the legislation and governance of esports. All the associations saw the lack, or fragmentation, of the national esports scene as a hindrance and were trying to develop that further by advising tournament organisers, setting up training for referees, and trying to ensure more fair treatment of players. Each representative also mentioned the “quite old people” (Macedonia) or “old structures in the ministry” (Austria) as a hindrance coming from governmental and/or sports decision-makers to accepting esports either as a sport or as a legitimate and worthwhile activity (depending on the association’s exact goals).

Differences among the eight associations surfaced as well. Naturally, since their national conditions, legislation, (sports) structures, and esports scenes vary, they also have different ways to operate in these respective environments. While France Esports has created a very structured organisation with departments or “colleges” that focus on individual issues (France Esports, 2023), the Finnish esports association was and still is organised like a typical association in Finland, with the board focusing on day-to-day operations and the members having power mostly through voting in two meetings per year to decide on general operational guidelines or directions. In both cases, the associations answer the local conditions and needs: France includes a variety of actors in their association and thus needs a more rigid structure, while Finland is set up as a typical (small) sports association.

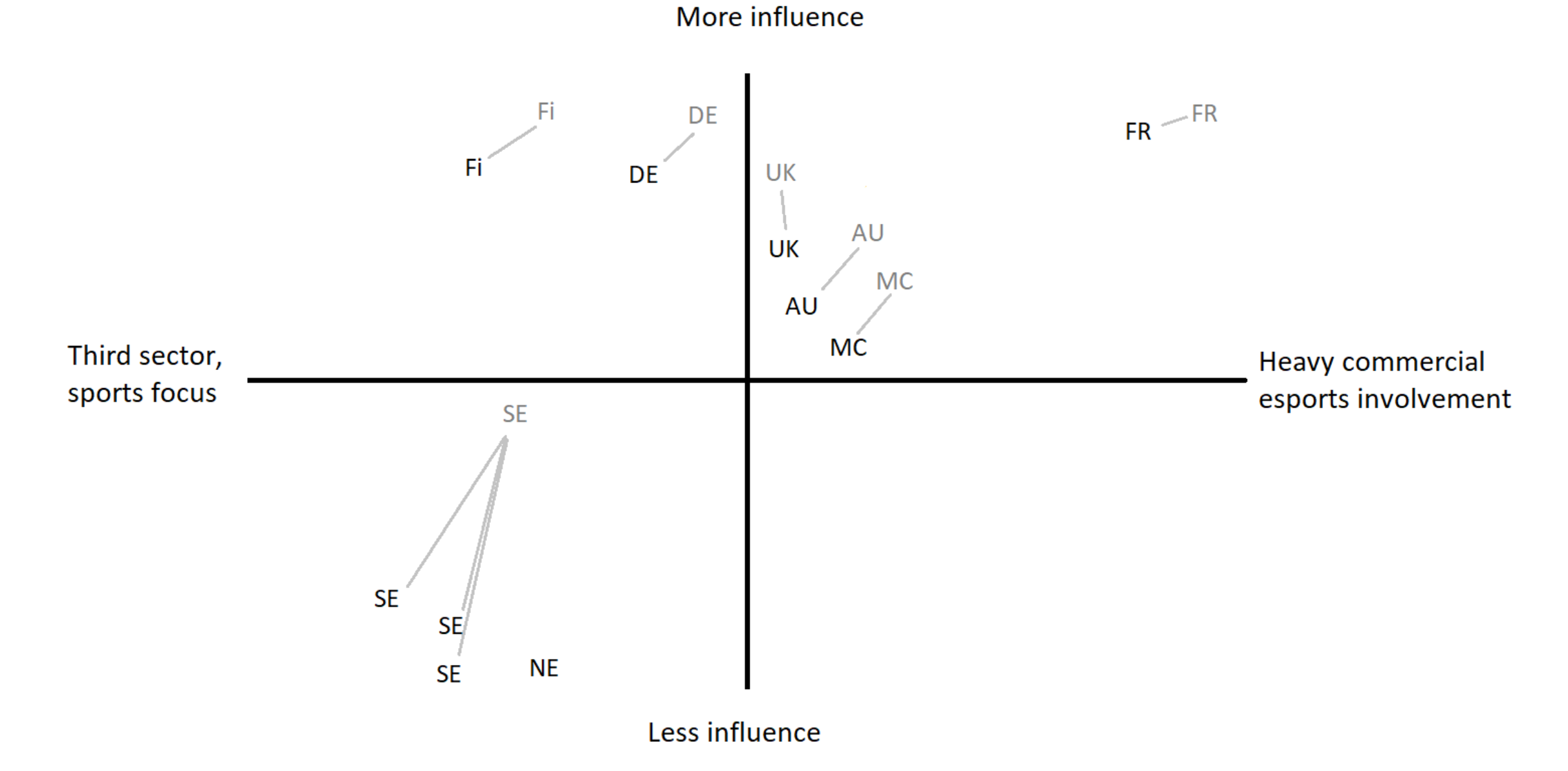

Taking all the results together, the differences among the associations can be synthesised into two vectors: the level of involvement from commercial esports and the level of power that the associations have in the esports scene, as well as in wider society (Figure 1). Positioning the associations within the two vectors highlights their major differences in composition and position in society, while still allowing a discussion of why certain aspects have led to success in some situations and not in others. The vector approach also allows for the analysis of change over time and differences in approaches to (common) national challenges.

Figure 1- Vector approach to esports associations. Initial positions of each association in relation to their level of influence and involvement of commercial esports and the direction of their development over the years. AU: Austria, DE: Denmark, FI: Finland, FR: France, MC: North Macedonia, NE: Netherlands, SE: Sweden, UK: United Kingdom.

Discussion

Not all associations in this study positions itself as a “sports association,” nor does it wish to join the local sports federations, but esports and traditional sorts are still converging as sports clubs establish and acquire professional and amateur esports teams and esports leagues and competitions are established in the same settings and contexts as traditional sports. As Dowling and colleagues (2018) note in their article reviewing comparative sports policy analysis, doing such research is difficult and challenging, especially as the number of included countries increases (Dowling et al., 2016).

Witkowski’s four categories acutely compare the mentioned associations to each other and allow for a starting point for further comparisons. If, however, the analysis were expanded to, for example, include all of the 137 national member associations in the International eSports Federation (IeSF, 2023), comparing and generalising would become difficult due to the number of associations and the relative rigidity and specificity of the categories. If one were to continue with the original four modes, it is likely that many associations would not fit them very well (e.g., the United Kingdom) and that many would fit several. If the number of categories increased there would be a danger of ending with almost as many categories as there are cases. Furthermore, the associations’ statuses change over time and the model gives few possibilities for comparing the developmental trajectories of the various associations, where they will go after the initial years and struggles, and whether their directions and paths are similar.

The global and international ecosystem of esports has been noted to be heavily controlled by game developers and other commercial organisations (cf. Scholtz, 2019; Karhulahti & Chee, 2020; Karhulahti, 2017). Similar concerns have also been raised in the national context of the United States, where numerous articles have called for more regulation to protect the players (cf. Holden et al., 2020; Murray et al., 2022; Chao, 2017). Witkowski also discussed the possibilities for players, especially minority players, to have their interests and concerns heard in the heavily industry-controlled French esports Association (Witkowski, 2022).

In associations like those of France, North Macedonia, and the United Kingdom, the esports industry is involved, and their interests are represented to some degree. Witkowski’s paper presents Esports France as an example of industry-mode associations, but, in addition, the substitute-mode association in Oceania was set up by the esports industry to ensure that its interests were met (Witkowski, 2022). A further example of an industry-led association is the Korean eSports Association, in which all sides of the esports industry have been involved since its founding in 2001 (Jin, 2010).

On the other end of the spectrum, the associations, especially from the Nordic countries, have noted that the esports industry in their national contexts does not really care or listen to the association. Finland’s few professional esports teams left the Finnish esports Association in 2019, as they felt that the association did not adequately take their interests into account. The Danish and Swedish associations both stated in the interviews that the industry was uninterested and uninvolved in the associations’ operations despite numerous tries to contact them.

While the involvement of the whole esports scene in each nation is likely to help increase the associations’ legitimacy and influence, a successful association does not necessarily need commercial esports. In Finland, the most prominent professional teams (ENCE, Havu Gaming, and hREDS) are still not members of the Finnish association. In addition, the developments in the Nordic associations also show that successfully working towards their goals and gaining legitimacy in the eyes of outside stakeholders, such as non-governmental organisations and governments, will also attract interest from commercial esports. For example, Esport Danmark is now working with professional esports teams in Denmark, and its board includes esports industry veterans (ESD, 2023). In a similar manner, now that the national scene in Sweden is cooperating under the association, the professional teams have also agreed to cooperate with them (although it must be noted that what this means in practice is unclear; SESF, 2022). The level of involvement from the industry marks a clear difference among the various associations that remains across national and contextual differences.

The second area where the associations had significant differences was their amount of influence in the esports scene and their perceived legitimacy. The eight associations are identical in their general aim of wanting to be the “voice” of esports in their national contexts. Be it the government, media, teams, players, or parents, the associations aim to be the entities that will be contacted with questions or for advice on specific issues. So far, the associations have also approached the need for advice and guidance in somewhat similar ways, at least with internal esports stakeholders: they provide guides, advice, checklists, rule sets, and other information on their websites for anyone to use who might need them.

In addition to the internal stakeholders and those whom esports affect directly, the associations have “been talking with” various ministries (e.g., France, the United Kingdom, and Finland), generally those sports and education related, “the government” more broadly, and actors from traditional sports federations and clubs. The associations are willing to talk with any stakeholder who seems to be willing to listen to them, and therefore the list of parties with whom they are talking is long. It is difficult to say, however, who is listening or how much actual influence the associations have in their national contexts, especially with governmental or other external stakeholders.

Nevertheless, some approximations regarding the varying levels of influence in countries are possible, depending on whether they have been able to fulfil their goals regarding external actors. In the case of those associations where the commercial esports are not members, whether the commercial side still respects their opinions. Of the associations that wish to join the national sports (con)federations, Finland, Denmark, Sweden and North Macedonia have reached this goal. Esports France seems to similarly have become the most influential party regarding esports in France, as both the government and esports scene regard it highly, according to the representative from France Esports. On the other end of the spectrum, the Netherlands (which was undergoing “major structural reorganization” at the time of the interview) is only just starting to work towards a more robust structure and role.

The concern for influence and legitimacy is essential for all the associations in this study, as well as in other studies, as they all aim to be the representative of esports in their respective countries. If they have no influence or support from the esports scene and are not seen as legitimate by outside stakeholders, they cannot be said to really be legitimate representatives. Thus, legitimacy and influence represent one important factor in discussing the development of and differences among esports associations.

Limitations

This study has weaknesses. Firstly, in most cases only one person from each national context and association was interviewed, and they were often people who wished to give as positive a picture of the association as possible. Interviewing more people, especially from outside the associations, could have resulted in different answers. Secondly, as the associations all come from Europe, there is a chance that more global data could have led to the inclusion of different dimensions in the framework.

Conclusions

This study focused on the various national esports associations in Europe. The associations have similar goals, aims and concerns regarding esports in their respective countries. They associated differ in two main aspects: the approach to commercial esports and level of power in their esports scenes. Using these two aspects, the developmental paths can be compared through a vector approach.

In the end, it remains difficult to adequately discern why certain differences and developments happen. Ideally, in future other studies will be able to further focus on either individual or selected countries, thereby allowing more specific issues in esports governance in those countries to be mapped. Nevertheless, the future path of (national) esports seems clear in one respect: the commercial or executive esports are unlikely to pass up the opportunity to exert their influence on any market that shows promising-enough growth, depth, and size. This is likely to happen in nearly any country that manages to grow their national esports scene robustly

Funding

This research has been funded by the Foundation for Economic Education (14-7649) and NOS- HS exploratory workshop on Nordic Esports.

Declaration of interest statement

The author confirms that there are no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Bojan, R. (2022); ЕСПОРТОТ СТАНА ОФИЦИЈАЛЕН СПОРТ ВО МАКЕДОНИЈА. Esports.mk. Retrieved September 8, 2023, from https://esports.mk/esportot-stana-oficijalen-sport-vo-makedonija/

- Chao, L. L. (2017). You must construct additional pylons: Building a better framework for esports governance. Fordham Law Review, 86, 737.

- Chee, F., & Karhulahti, V. M. (2020). The ethical and political contours of institutional promotion in esports: From precariat models to sustainable practices. Human Technology, 16(2), 200.

- Dowling, M., Brown, P., Legg, D., & Grix, J. (2018). Deconstructing comparative sport policy analysis: Assumptions, challenges, and new directions. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 10(4), 687–704.

- ESD (2023) Board of Directors. Esport Danmark. Retrieved September 8, 2023, from https://esd.dk/referater-bestyrelsesmoeder/

- Holden, J. T., Edelman, M., & Baker III, T. A. (2020). A short treatise on esports and the law: How America regulates its next national pastime. University of Illinois Law Review, 509.

- IeSF. IeSF Members. Retrieved September 8, 2023, from https://iesf.org/members

- Jin, D. Y. (2010). Korea’s online gaming empire. The MIT Press.

- Karhulahti, V. M. (2017). Reconsidering esport: Economics and executive ownership. Physical Culture and Sport. Studies and Research, 74(1), 43–53.

- KeSPA. Korean eSports Association. Retrieved September 8, 2023, from http://www.e-sports.or.kr/?ckattempt=1

Appendix 1

Semi-structured question-frame for the interviews.

The question frame was used as a starting point for the interviews and more detailed

questions were asked in response to the interviewees to gain more information and

explanations. The questions were also partly tailored to fit the situation of each association.

-

History of esports in [country]

- Please, tell freely, of the early days of esports in [country]

- When were the first competitions?

- Were there gaming magazines etc that would collect highscores?

- Any knowledge on the arcade scene, or magic the gathering? Were they active?

- Did early esports have something to do with demoscene? Or were they tied to some other computer- or gaming events?

- When did players and others start to take competitions ‘seriously’?

- Do you have any numbers over the years? Players, competitions, winnings, events, etc.?

- Has the government had initiatives that helped esports?

-

History of the association

- When and why was the association established?

- Who were the ones to found it?

- What was it like before the association? What need did it answer?

- What did it aim to do? Are the aims still same?

- What major accomplishments has the association had over the years?

- Any bigger setbacks?

-

Current situation of the association

- What does the association exactly do these days?

- Are you set up like a typical sports association in [country]

- Do you have any numbers for current competitors/players/esports participants?

i. Is there some kind of registry for the players? How does it work? How was it created? When/Why? Does it cost to join? - Do you offer some sort of training? What kind? Why/what need does it answer?

i. For whom? Players, referees, teams, management? - Do you have consultation services for organisations/players etc. ?

i. What kind? - Have you made standardised rules for games/tournaments? Where can they be found?

- You are a full member of the international eSports federation? What does this mean to the association? [if appliable]

- Are you a member of the [national] sports confederation?

- What kind of international projects/cooperation do you have?

- How does the association finance its work? Has this changes over the years? i. Do you have any paid employees or just volunteers?

- How do you think the association fits the national esports scene?

i. How much influence do you have/are you important?

ii. Do players/teams/government/etc listen to you? - What do you think are your advantages/disadvantages compared to other national esports associations and their scenes?

-

Esports currently in [country]

- How are things? Please speak freely

-

How many competitions, players, etc. Numbers

i. Women, age, money in, teams, sports teams in esports, prize money, etc…

ii. Any mobile esports? - Who organizes the competitions? Non-commercial/commercial organisers, how many, etc.

- Do you have ‘official’ national leagues? Which games? How did things go? How many competitions/teams, price money etc.?

- Is the esports scene organized in the same way as sports /(youth) sports generally?

i. Does it operate in similar way? - Are there a lot of sports teams that have entered esports?

- Is esports seen as an official sport in [country]? If not, what’s missing? If yes, what was required to get there?

- How does the government view esports?

i. Are players treated as athletes or something else?

ii. Does the government support the esports scene in some way? - How does the public see esports?

- How common are the negative aspects of sports in [country’s] esports? Cheating, doping,

etc.

i. Do you have doping control? - What is good in [country] esports?

- Bad? How could that be changed?

-

Future of esports in [country]

-

What do you think will happen with the association in the future?

i. What will change in your operations? - Esports in general: An accepted part of sports, something similar, a niche thing?

- What do you think about esports entering olympics?

- What things do you think the future development will depend on? What will be the deciding factors?

- What do you think about the influence game developers have in esports? Does it affect esports in [country]? Will this change in the future?

- Do any wild cards etc come into mind that could change the development of esports in unexpected ways?

-

What do you think will happen with the association in the future?