Sportification of Esports - A systematization of sport-teams entering the esports ecosystem

by Tobias Scholz*, Lisa Völkel, Carolin UebachEmail: Tobias.scholz@uni-siegen.de

Received: 25 Nov 2020 / Published: 21 Apr 2021

Abstract

Esports has gained much attention in recent years and mainly traditional sports clubs see esports as a way to diversify their product or brand. This is because many traditional sports are often failing to attract a young audience. Furthermore, they need to catch-up concerning digitization and internationalization. All of these aspects are substantial parts of esports. Therefore, over 400 professional sports clubs at the end of 2019 entered esports. However, there is no single strategy observable. Consequently, the goal of this paper is to systemize sports teams in esports. Based on that analysis, three cases will be presented to show the potential struggle in joining esports and why sports need to establish a strategy for entering esports. Finally, several implications for sports teams will be presented to minimize the risk of entering the esports ecosystem.

Highlights

- Until 2019, 418 traditional sports teams entered esports and after a peak in 2018, the number of teams is diminishing.

- We propose a systematization of these sports teams into eight types based on Scholz’s seven types expanding the typization with individual investors.

- The cases of SSV Lehnitz, FC Schalke 04 and Paris Saint Germain highlight unique strategies for sports teams entering esports.

- Esports can help revitalize traditional sports, reach a young audience, and venture into the digital society. But it all depends on a precise strategy from the sports business. If that is not happening, it could hurt the traditional sports teams.

Link to sports teams in esports database:

http://sports.esportslab.org/Introduction

In recent years, esports has grown exponentially (Scholz, 2019; Taylor, 2012) and attracted interest from various non-endemic actors. Besides companies like Amazon buying the live streaming platform Twitch and media companies like Modern Times Group acquiring ESL and Dreamhack, there is a surge of sports organizations joining esports. Esports has been evolving for a long time, mostly in isolation, but this has changed significantly in the last years. At the end of 2019, more than 400 sports teams worldwide have communicated that esports is part of their sports organization. The strategies vary from teams like FC Schalke 04 having a League of Legends (LoL) Team on the highest level to Eintracht Frankfurt fostering esports on a more grassroots and local level.

Just recently, in August 2020, the Rhein-Neckar Löwen announced their ERN ROAR team and made a call for local League of Legends players (Rhein-Neckar Löwen, 2020). At the same time, VfB Stuttgart closed their esports team due to the Covid-19 crisis (Sieroka, 2020). Those two examples reveal the difficulty in creating a successful esports team. Covid-19 reinforced the risk of the current sports business model and amplified how frail it is (Goldman & Hedlund, 2020). Consequently, there is a certain allure to venture into esports, especially as it seems resistant to this crisis (Rietkirk, 2020), at least, more resistant than traditional sports. Furthermore, many traditional sports struggle to reach the young generation (Lombardo & Broughton, 2017), and esports seem to be more successful (de Freitas, 2021). From a business perspective, it makes strategic sense to invest in esports.

Still, the case of VfB Stuttgart reveals that esports is a complex and volatile ecosystem. There is no concise or unified strategy to succeed in esports and sports are, in a certain sense, deadlocked due to their long history. Even though sports teams have many tools to be successful in esports, many organizations venture without a strategy into esports. Researching the existing sports organizations should be helpful to understand the sportification of esports. It is essential to highlight that this is a global competition and sports teams compete with other sports teams, existing esports teams, and various investors and businesses. The market is far from divided up and, consequently, highly competitive

In this paper, the goal is to give some form of systematization for sports teams joining esports until the end of 2019. Based on the types of sports teams in esports from Scholz (2019), the authors systematically searched for those sports teams and categorized them. These results yield an overview of the current stage and serve as the basis for three unique cases of interesting sports teams joining the esports ecosystem. Finally, implications will be discussed on how to adequately venture into esports and highlight the importance of strategic management. Being a successful sports team does not translate into definite success in esports.

Sports and Esports

There is a longstanding and highly debated discourse if esports is a sport (e.g., Cunningham et al., 2018; Franke, 2015; Hallmann and Giel, 2018; Holden et al., 2017a,b; Hutchins, 2008; Jenny, Manning, Keiper & Olrich, 2017; Jonasson & Thiborg, 2010; Parry, 2019; Rosell Llorens, 2017). There is an observable link to sports based on competitiveness and how the tournaments are designed (Adamus, 2012; Hebbel-Seeger, 2012). Even though there might be sufficient parallels to call esports a sport, many sports associations like the International Olympic Committee are cautious and try to dictate the rules for the inclusion of esports in the sports world (Bates, 2019). For esports, being a sport may lead to a wide-spread legitimation and legal certainty; for traditional sports, it might lead to a loss in their current power situation (Scholz, 2019).

It is essential to highlight that esports may not fit into the category of traditional sports, as “to think that a new phenomenon like esports can be described in terms of the old is to misunderstand it entirely” (Superdata, 2015, p. 3). Esports emerged out of a digital phenomenon and is intertwined with globalization. The core of esports is the idea that everybody can play with everybody around the world. Traditional sport, however, is, at its core, about the physical and local interaction. This core difference influenced the evolution of esports fundamentally: Esports is born digital and born global (Scholz, 2019). Therefore, we are using the following definition for esports: “Esports is a cultural phenomenon with resemblance rooted in sports, media, entertainment, and culture, but emerged in a digitized environment. Thereby, evolved beyond the constraints of traditional sports, media, entertainment, and culture.” (Scholz, 2020).

Despite the ongoing discourse on sports and esports, it is undeniable that there is a surge of interest in esports from sports organizations. Various sports businesses have invested heavily in esports in the last couple of years. Although, on a local level, many sports teams are adding esports due to their societal tasks for the community, many sports businesses see esports as another market with growth potential. Consequently, there is a strong business interest in venturing into esports. This development can be observed with the strategic partnership between FC Barcelona and Tencent (Hitt, 2020).

In addition to searching for new growth possibilities, many traditional sports struggle to connect with a young audience. A study by Lombardo and Broughton (2017) stated that the average age is gradually increasing in all major US leagues. For example, the National Football League fan's average age rose from 46 years in 2006 to 50 years in 2016. Every other big sport has fans averaging beyond 40 years with Major League Baseball at 57 years. On the other side, the average esports fan is at 29 years (Sims, 2020). Although data collection in esports is still not as reliable as sports data, the difference is striking. The underlying assumption is that esports might revitalize traditional sports and introduce esports fans to traditional sports. It is essential to highlight that the potential of such synergy effects needs to be addressed in the esports business development strategy. However, there are various strategic approaches observable within sports teams entering esports. Scholz (2019) derived the following seven types for sports teams investing in esports:

- “Individual (esports) players for the digital version of the core business.

- Esports teams for a variety of games.

- Esports teams for a variety of games in a different country.

- Joint ventures with an existing esports team and creating a new brand.

- Temporarily withdrawing from esports.

- Creating a dedicated league.

- Buying a franchise team.” (Scholz, 2019, p. 78-79).

Type 1 describes the strategy of teams to identify esports players playing their sport virtually. These players represent the team and often wear the official jerseys. Type 2 teams are playing different esports titles besides their sports. The most prominent example is FC Schalke 04, having a successful League of Legends team and football esports players. Interestingly, they keep the brand to create synergies between the football division and the esports division (Reichert in Elsam, 2018). Type 3 is a rarity but a strategy to access new markets. One case is Olympique Lyon signing a Chinese esports team as part of its internationalization strategy. This strategy was perceived as “a fascinating move by Lyon and a logical attempt at growing its brand overseas and reaching a whole new fan base” (Cooke, 2017). Type 4 is about keeping the brands separated but utilizing potential synergy effects. One example of that is the Counter-Strike team North from FC Copenhagen. Type 5 needs to be mentioned as there are various cases in which a sports team withdraws from esports, which can be temporary. Type 6 is currently the most common form in which a league is created mimicking the traditional sports counterpart. This is often spearheaded by the league operator, for example, the Virtual Bundesliga in Germany consists entirely of teams from the 1st and 2nd Bundesliga. Type 7 has gained more attention recently as many esports leagues, like League of Legends and Overwatch, are adopting the franchise model. In Overwatch, for example, the Comcast Group owning the Philadelphia Flyers acquired the Philadelphia Fusion. In League of Legends, Golden State Warriors invested in the Golden Guardians.

In recent years, another type emerged (type 8). A growing number of individual sports players and individual investors affiliated with sports invest in esports teams (e. g. Stephen Curry investing in TSM) or even create a team (e. g. the footballer Christian Fuchs). This trend gained momentum only recently in 2019. Still, big names such as Michael Jordan (Forbes, 2018) use their fortune to diversify their portfolio into esports. As anybody can invest in esports and many professional sports players play video games, type 8 is expected to grow exponentially in the coming years.

With this process of sports teams venturing into esports, it could be assumed that there is a sportification in esports. Sportification is described by Crum (1993) as a development in which a group is sportified over time. Heere (2018, p. 23) defines sportification as “(a) view, organize or regulate a non-sport activity in such a way that it resembles a sport and allows a fair, pleasurable, and safe environment for individuals to compete and cooperate, and compare their performances to each other, and future and past performances; or (b) add a sport component to an existing activity in order to make it more attractive to its audiences.” It is observable that sports impact esports. Scholz (2019) mentions that there are sports-driven business models in the esports ecosystem, leading to a sportification of the business perspective in esports. That is also highlighted in Lefebvre et al. (2020) research. They research how football clubs utilize their esports strategies, focusing on dynamic capabilities and the sense-seize-transform model. It becomes evident that there is a sportification process ongoing in terms of organization and regulation, but mostly by increasing the sportiness in esports (Witkowski, 2010).

Methodology

The process of finding sports teams that entered esports was done exploratory, especially as there is no concise list for such teams. Many lists are vastly incomplete, which can be seen in the case of SSV Lehnitz, which is not listed in any of the existing reports. The data was collected between 2017 and 2019 and we used esports news sites Dexerto, Dot Esports, ESPN, Esports Insider and The Esports Observer. Furthermore, we utilized the snowball method (Baltar & Brunet, 2012) to search for additional sports teams by using search engines, social media, and traditional sports news outlets. As esports is still emerging and there are no centralized institutions like sports associations that may collect such data, we utilized the snowball method to follow up on news snippets and posts. We cross-referenced this with other data sources to confirm the information. Based on this information, we searched for the original news or press release on the sports teams' webpage to verify the news. Finally, we cross-checked it with the list of Code Red Esports that emerged in 2019 and validated some of the entries. Consequently, the list may be incomplete as the search process is limited and language barriers might lead to teams missing. It might be the case that there is a vast amount of sports teams in countries like China, however, it is recommended that esports data from China be utilized with caution (Fragen, 2018). Still, the data-set is, at the moment of publication, the most exhaustive data-set available.

Results

Descriptive Analysis

In the search process, we identified 418 sports teams and individual sports investors that have entered esports in some form until the end of 2019. It became evident that some teams could be part of various categorizations as the systematization of Scholz (2019) is no longer precise enough due to esports' evolution. Esports is highly volatile and this volatility is even further increased by the hefty influx of various sports teams. The sportification of esports may stir up new evolutions and, subsequently, new types, like type 8 we introduced in this paper.

As shown in Table 1, most teams come under type 1 (101 teams) and type 6 (189 teams). These types are an extension of the sports that teams play in the esports simulation of that specific sport. Most of these teams are from football. However, there is one distinct difference between those types. In countries like Germany, the initiative for expanding to esports is driven by individual teams. Consequently, several top teams, like Borussia Dortmund, are still missing in the Virtual Bundesliga. That team saw esports not as part of their strategy for a long time and even stated in 2016 that Borussia Dortmund will not enter esports as it may weaken their brand strategy (Begehr, 2016). However, they added a FIFA player and entered esports in 2020 (Oezbey, n.d.). In countries like Japan, the initiative is driven by the national sports association, subsequently stating that every team in the first and second division of the J.League will have to participate (Konami, 2019). Therefore, this type inflates the number of teams involved in esports. Nonetheless, the brand is still represented in esports and impacts the strategy of the respective sports teams.

Table 1 - Typification of Teams.| Type | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| (1) Individual (esports) players for the digital version of the core business | 101 | 24,16% |

| (2) Esports teams for a variety of games | 50 | 11,96% |

| (3) Esports teams for a variety of games in a different country | 2 | 0,48% |

| (4) Joint ventures with an existing esports team and creating a new brand | 9 | 2,15% |

| (5) Temporarily withdrawing from esports | 13 | 3,11% |

| (6) Creating a dedicated league | 189 | 45,22% |

| (7) Buying a franchise team | 25 | 5,98% |

| (8) Individual investors | 29 | 6,94% |

| Total | 418 | 100% |

More interesting from a brand perspective and the strategic diversification of traditional sports teams are the types 2 (50 Teams) and 7 (25 Teams). Especially with the introduction of the Overwatch League and the success of League of Legends, many sports teams saw an opportunity to invest in esports and, by that, achieve diversification of their portfolio. This situation intensified with the recent move towards franchising in esports. Sports groups from the U.S. saw the parallels to leagues like the NFL and NBA, leading to many of those teams investing in the Overwatch League and the League of Legends Championship Series. For example, Kroenke Sports and Entertainment owns Arsenal London, Colorado Avalanche, Colorado Rapid, Denver Nuggets, and Los Angeles Rams. They acquired the Los Angeles Gladiators in Overwatch. There are observable strategic and administrative synergies like the Dallas Cowboys, who own Complexity and support them in terms of training facilities. It remains unclear how much sports teams can utilize the synergy effects if they have different names and brands. Or is the bet to have an alternative for the time if traditional sports continue to lose their attractiveness?

Type 3 (2 teams) is still an odd strategy for many teams; however, there are two teams (Olympique Lyon and Paris Saint Germain) focusing on that strategy. Interestingly both teams are from France and, in the case of Paris Saint Germain, they are incredibly successful. Concerning type 4, this has become less popular in recent years as many sports teams are nowadays trying to create their department for esports in their organization. But there may be a “dark number” of sports teams giving their name to esports teams or individual players managed by another organization.

Teams withdrawing from esports (Type 5) have happened occasionally but may increase in the near future. Cases like VfB Stuttgart show the struggle to adapt to esports and the necessity of a strategy. As many sports teams realize, it requires a significant investment to be on the toplevel in relevant esports titles like Counter-Strike. In other titles like League of Legends that are franchise leagues, the slots are limited. Consequently, the cost-benefit-analysis might not be beneficial for several esports programs from traditional sports teams, especially as it is still questionable if the proposed synergies from esports to sports really loom the way it was envisioned.

In our research, this became evident with type 8 in which individual players and individual investors who are affiliated with esports are investing in esports and utilizing their money to become shareholders of traditional esports teams like Earvin “Magic” Johnson investing in aXiomatic, which owns Team Liquid, or create their own team like David Beckham with Guild Esports (Seck, 2020a)

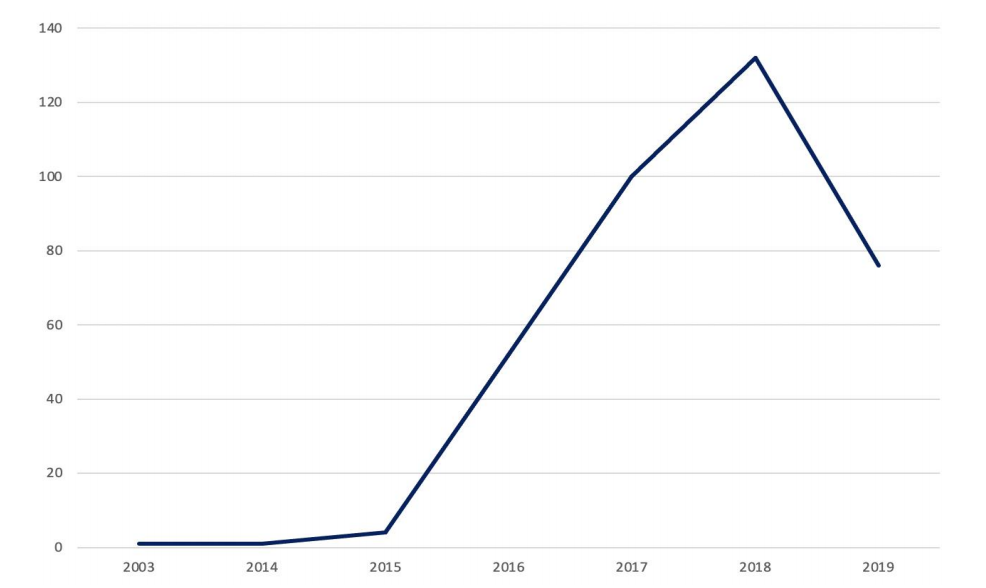

As mentioned earlier, the recent influx of sports teams entering esports started in 2015 (Scholz, 2019; Lefebvre et al., 2020). SSV Lehnitz was an extreme outlier with their experiment in esports from 2003 until 2006. Interestingly, in 2014 the American Football player, Roger Saffold, acquired a Call of Duty squad, became the first individual investor from sports, and predates sports teams' interest in esports. However, the numbers indicate that the peak was reached in 2018 and 2019 was already a bit slower, illustrated in Figure 1. That may be because sports teams do not see the immediate success of having an esports team and the increase of investment necessary to achieve high-level success. However, in 2019 and 2020, we see that sports teams no longer focus on the highest level but try to complement their regional impact, e.g., Eintracht Frankfurt with a local League of Legends team and the collaboration of FC St. Pauli with the team MTW Gaming in League of Legends. Both teams try to succeed nationally in competing in the Prime League.

Concerning those sports teams' origin, the U.S. is currently the most prominent region for traditional sports teams in esports, with 70 teams. This has recently increased with the investment of various individual sports players. Following up, there is Japan, but that is due to the push of J.League that already contributes 40 teams in that number. Germany is in third place with 44 teams, however, mostly with football teams. In the following, there is England, Netherlands, France, Norway, and Belgium. There is a strong European focus, however, that may be due to the research focus on Western media as China is only listed with two sports teams. But it is interesting to observe that many countries are following specific sport cultural values. The U.S.A. focuses on franchise leagues and teams part of such leagues, Germany with a more individualistic bottom-up approach, and Japan with a collectivist top-down approach.

Figure 1 - Entrances per Year.

Case of SSV Lehnitz

Many articles are stating that sports teams started to move into esports in 2015 and the first big mover was Besiktas Istanbul (e.g., Oelschlägel, 2015; Wochnik, 2015). Besiktas Istanbul is often considered as the first sports team in esports on a professional level. However, the first sports team in esports was a German organization called SSV Lehnitz in 2003. Although Lehnitz might not be a big sports name like Besiktas Istanbul or Paris Saint Germain that joined esports early on (Paspalaris, 2016), SSV Lehnitz was a powerhouse in Counter-Strike from 2003 until 2006 with playing at the World Cyber Games in 2003 in Korea and the CPL Brazil in 2005. Furthermore, the team always had an international focus with players from Austria and Sweden as well as a multi-gaming strategy with teams in Counter-Strike, Warcraft 3, and Battlefield.

It is essential to highlight that sports teams still struggle with Counter-Strike as part of their organization; therefore, it is important to emphasize that in 2003, Counter-Strike was depicted as a “killer game” in Germany. SSV Lehnitz added esports into their organization to make their brand internationally known, reach a young audience, attract new sponsors, and improve their image as well as the image of esports (Gamesports, 2003). This organization was already pioneering the sports-esports discussion before any other sports team even considered it. SSV Lehnitz exited esports in 2006 (Scholz, 2019) due to the following reasons summarized by the board member Norbert ‘roofman’ Skrobek: “The main problem arising at the moment is that we’re not able to form contracts with players, since we are a non-profit organization. Also, we have to heed the many obligations of the German legal framework, that are counterproductive for our endeavors” (Skrobek in Hiltscher, 2005). Nonetheless, this case highlights that the reasons for joining esports are today still the same. In addition, the synergy between esports and sports becomes apparent as sports organizations help to legitimate esports and many regional newspapers reported optimistic about this development. This case also shows the struggle for any sports team in esports. Esports is dynamic and highly volatile, SSV Lehnitz struggled in Counter-Strike to keep players for an extended period and the squad consistently changed (Liquipedia, n.d.). SSV Lehnitz is the first and prime example of sports teams joining the esports world. And it is a striking sign of historical amnesia (Scholz, 2019), as this case is often forgotten in the current discourse.

Case of FC Schalke 04

Another pioneer in sports expanding to esports is FC Schalke 04. This football team joined esports in 2016. However, not only for the football simulation as many others, but they also focused on League of Legends and, even further, strived to compete on the highest level. The team even bought a franchise slot for the League of Legends European Championship, intending to compete on a global level and qualify for the World Championship: “From a business point of view, if we go to Worlds, this would mean so much to the club. It would be massive to have a global audience, global eyeballs everywhere with millions of people” (Reichert quoted in Elsam, 2018). In the 2020 summer season, the LoL team even became an Internet phenomenon as they qualified for playoffs after a record losing streak. The “Schalke 04 Miracle Run” led to a massive gain in interest in Schalke on a national and international level (e.g., Graeber, 2020; van den Bosch, 2020). The LoL team has been able to push the brand to new levels and new markets.

It is part of Schalke's strategy to bring fans from sports and esports together and already in 2017, the LoL team walked on the football pitch and were presented in front of thousands of fans (Anastasopoulos, 2017). Furthermore, Schalke sees an intersection between both fan camps and the core of the strategy is creating synergy by utilizing the existing brand. Currently, the majority of sports teams owning a team outside of their sports simulation counterpart are using different brands like the Kraft Group that owns the New England Patriots and the Overwatch Team Boston Uprising. FC Schalke 04 states that they want to integrate esports in its entirety to the Schalke family (Reichert in Nermerich, 2019). This might be a bet for the future, but with the exponential growth of video gaming, the potential of brand synergy can only grow. Still, it needs to be proven that esports fans can become sports fans and sports fans can become esports fans (Schmidt & Holzmayer, 2018). But, FC Schalke 04, as an early adopter, positioned themselves strategically with League of Legends that will lead to sustainable success in the long run.

Case of Paris Saint Germain

Another interesting case is the esports commitment of Paris Saint Germain (PSG) and its drastic strategic changes. PSG entered esports around the time of FC Schalke 04 in 2016 and it even led to matches between both teams in League of Legends (von Au, 2017). However, as Riot moved towards a franchise model for the European league, the management decided to withdraw their team: “Our Challengers Series experiences lead us to wonder about the League of Legends competitive scene economic balance” (PSG, 2017). In that time, there was an ongoing discussion about the profitability of League of Legends on the highest level and a debate about the revenue sharing model offered by Riot Games (Handrahan, 2017). It seemed that PSG made a strategic decision due to the deficit cost-benefit-outlook for the future of the team, especially as they did not show the results. Still, PSG stayed in esports with rosters in FIFA and Rocket League. With the brand exiting Rocket League in 2019.

PSG's strategy is always to compete on the highest level, as is the case in football or handball. Therefore, they had a close look at esports, which may have prompted their exit in League of Legends. This strategy also led to the decision to partner up with the Chinese esports organization LGD Gaming in DOTA 2 in 2018. The organization highlighted in the announcement that this move is part of their strategy to “open the way to the Asian continent but also Eastern Europe or North America where DOTA is very well established” (PSG, 2018). They were able to reach The International's finals (the biggest Dota 2 tournament of the year) in the same year. Co-aligning to the strategy of utilizing esports to move towards the Asian market, they announced a partnership with the Hong Kong organization Talon Esports and reentered League of Legends in 2020. Furthermore, they highlighted this cooperation is part of its brand diversification strategy (PSG, 2020). Besides the FIFA players, the focus of PSG is entirely on the Asian market and esports serve to expand the reach of the brand and foster growth.

Discussion

It becomes evident that there are various strategies to enter esports as a sports team, however, it also comes as some countries are pushing more aggressively into esports. Especially in the US, sports teams see esports as chance to diversify and to conquer new markets. In this paper, we only looked at sports teams, but there is also a surge in collegiate esports teams, and many colleges are trying to establish esports teams in their varsity program (Johnson, 2020). Thus, the number of sports programs being involved in esports is higher than reported in this paper. Furthermore, it seems surprising that Germany has so many sports teams in esports, even though the legal situation of esports as a sport is still debated. Nevertheless, the list is still missing several sports teams, and especially in countries like China, there will be more than a few sports teams venturing in esports. Consequently, a limitation of the paper is that the number of sports teams will be higher, but, to our knowledge, this list is the most exhaustive one to date. Furthermore, data collection has been done until the end of 2019.

Interestingly, it becomes apparent in 2020 amid the current Covid-19 crisis that sports teams reevaluate their engagement in esports, and teams like VfB Stuttgart exited esports entirely. There might be further changes in the sports-lead esports teams as in leagues like Overwatch or Call of Duty, where the concept of geolocalization is currently not conductible. Furthermore, Teams like the Philadelphia Fusion are building esports arenas that they cannot currently make use of. Even though Overwatch teams are locked in to the franchise model, they will not exit the league in the short-term but will revaluate their financial commitment. It becomes apparent that having an esports team does not magically lead to monetary gain or attracting young audiences.

In many cases, sports teams still shy away from committing to esports fully and, by that, use the existing brands for recognition. A development that was observable with Clutch Gaming, owned by Houston Rockets. Clutch Gaming was sold in 2019 to the Philadelphia 76ers and was renamed Dignitas (Wolf, 2019). Although the synergies still do not exist between 76ers and Dignitas, the brand Dignitas is a well-known name in esports as it was founded in 2003. Only a few teams utilize their branding's full synergy potential and for FC Schalke 04, it seems to work (Schmidt & Holzmayer, 2018). Besides this defensive behaviour, there is also inconsistent behaviour observable. PSG started with acquiring a League of Legends team and had a match against FC Schalke 04 but exited the market only to rejoin esports with a joint venture with the Chinese Dota 2 team LDG Gaming in 2018 and in 2020 the partnered up with the Hong Kong League of Legends Team Talon Esports. PSG is an example of the inconsistency of various sports teams in esports.

It becomes evident that there is a sportification in esports observable, and many sports companies are trying to transfer the competences adequately. However, this makes sense in adding the sport component as depicted in Heere (2018) and the utilization of sports knowledge. From a regulatory and management perspective, various challenges hinder the sportification of esports. (1) Esports is influenced not only by sports but also by media, business, entertainment, game developers, and existing esports organizations. That lead to a competition between various approaches of regulating esports distinctly (Scholz, 2019), (2) there is no consensus on how to deal with esports from sports associations as seen in the ‘is esports a sport’ discourse (e.g., Pack & Hedlund, 2020), and (3) there are regional differences in the approach of sportification, be it the franchise-strategy in North America, or the grassroots club approach in Europe, or the sport's development strategy in Asia-Pacific as described in this paper with the case of Japan. There is a clear sportification observable, however, the strategies vary vastly. The presented cases showed three different strategies, despite the fact that two are from Germany and two have their core business field in football. The global esports ecosystem is still in flux and sportification is just one influence of many.

Still, esports could serve many purposes, especially acting as a future lab for digitizing their sports business and a testing field for new ideas. Especially as the esports audience is younger than the sports audience, this might yield success and lead to synergies between the audiences. Esports can help to reverse the age development of traditional sports. Furthermore, in theory, the running costs are relatively low as the sports training facilities can be used by the esports players as well as the staff. Beyond that, with the progress in technology, such as virtual reality becoming more common, there might be a future in which any sport could be played virtually. Building up knowledge and competencies for the digitization now will translate into a competitive advantage if Sports is moving to Sports 2.0 (Miah, 2017).

Esports will keep on growing, however, it will also diversify even further. New esports titles will emerge and others will vanish (Scholz, 2019). With the current franchising model prevailing in the big leagues, it will become expensive for sports teams to join on the top level. Especially for early adopters like FC Schalke 04, this could translate into long-term success. But, if leagues are struggling like the Overwatch League, this could also tarnish sports teams' long-term commitment. If such an expensive franchise league would fail, this may also lead to an exit of individual sports businesses in the esports industry (Scholz, forthcoming). It becomes evident that esports stay volatile for sports businesses as there is a high fluctuation in esports titles. An esports title like Valorant officially released on the 2nd of June 2020 is already categorized as a Tier 2 esports title (Seck, 2020b). Consequently, picking the right game and the right franchise is a huge source of risk. Coming from traditional sports, the competence of selecting such a game is nothing that traditional sports teams or sports businesses possess.

Consequently, it will be crucial to find the right people before venturing into esports (Scholz & Stein, 2017). There is a lot that esports can learn from sport, be it training, marketing, merchandise, and many other elements. However, this is not unidirectional. Esports has its own rules (Scholz, 2019) and follows a digital mindset. Understanding this difference and that not everything that works in sports will work in esports will be the competitive advantage for sports businesses entering the esports ecosystem. Therefore, refusing to learn “esports” may endanger the business (Mom et al., 2015). Furthermore, this lack of willingness to learn, as the sports executives are doing a great job in sports, might also rob them of the innovativeness of esports and the chance to digitize their business and reach a younger audience.

Conclusion

The debate if esports is a sport may never end, however, it is unnecessary to have an uncompromising stand on this question. It becomes evident that esports is interesting for sports teams. Be it the local sports club serving their community or the sports business diversifying their portfolio. Esports are different and this difference can be utilized for innovations, especially as some sports reach a dead end. Esports can help revitalize traditional sports, reach a young audience, and venture into the digital society. But it all depends on a precise strategy from the sports business. VfB Stuttgart may be only the beginning of sports teams’ exiting esports as many jumped on the bandwagon. There are many synergies for sports teams to have a head start to other investors, but in the long run, this can lead to a lock-in in which they are doing esports their traditional sports way.

Acknowledgements, Funding, Declaration of interest: NoneReferences

- Adamus, T. (2012). Playing computer games as electronic sport: In search of a theoretical framework for a new research field. In J. Fromme, & A. Unger (Eds.). Computer Games and New Media Cultures: A Handbook of Digital Game Studies (pp. 477-490). Dordrecht: Springer.

- Anastasopoulus, A. (2017, December 13). Schalke 04 Will Present League of Legends squad in Front of Thousands of Soccer Fans. Retrieved from https://esportsobserver.com/schalke-04-presents-squad-to-soccer-fans.

- Baltar, F., & Brunet, I. (2012). Social research 2.0: virtual snowball sampling method using Facebook. Internet Research, 22(1). 57-74.

- Bates, P. (2019, December 13). Olympics will only incorporate esports simulation titles. Retrieved from https://www.sportspromedia.com/news/olympics-esports-simulationioc.

- Begehr, J. (2016, November 22). Darum begeht Watzke einen folgenschweren Fehler. Retrieved from https://www.welt.de/sport/fussball/article159668692/Darum-begeht-Watzkeeinen-folgenschweren-Fehler.html.

- Code Red Esports (n.d.). Sports teams in Esports by Redeye. Retrieved from https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1qkr79b8V3GR2Uk2ZYCzeccm7oWWeNV72T ZRKOL_Khbg/edit#gid=0.

- Cooke, S. (2017, March 10). Olympique Lyonnais launch FIFA esports team in Beijing. Retrieved from https://www.esportsinsider.com/2017/03/olympique-lyonnais-launchfifa-esports-team-beijing/.

- Crum, B. (1993). The sportification of the society and the internal differentiation of sport. In: EASM (Eds.). Proceedings of the first European congress on sport management (pp. 149- 153). Groningen: European Association of Sport Management.

- Cunningham, G. B., Fairley, S., Ferkins, L., Kerwin, S., Lock, D., Shaw, S., & Wicker, P. (2018). eSport: Construct specifications and implications for sport management. Sport Management Review, 21(1), 1–6.

- de Freitas R. (2021) Gen Z and esports: Digitizing the live event brand. In W. Wörndl, C. Koo & J. L. Stienmetz (Eds). Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2021 (pp. 188-201). Springer, Cham.

- Elsam, S. (2018, August 27). Tim Reichert, FC Schalke 04 Esports—Traditional teams need to approach esports in a ‘bigger way’. Retrieved from https://esportsobserver.com/timreichert-schalke-04-interview.

- Forbes. (2018). Michael Jordan Enters Esports, Invests In Team Liquid's Parent Company. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/mattperez/2018/10/25/michael-jordan- enters-esports-invests-in-team-liquids-parent-company/

- Fragen, J. (2018, June 15). MSI 2018 shows why you should be skeptical of esports viewership statistics. Retrieved from https://esportsobserver.com/opinion-esports-viewershipmsi-2018.

- Franke, T. (2015). The perception of eSports – Mainstream culture, real sport and marketisation. In J. Hiltscher & T. M. Scholz (Eds.). eSports yearbook 2013/14 (pp. 111–144). Norderstedt, Germany: Books on Demand.

- Goldman, M. M., & Hedlund, D. P. (2020). Rebooting content: Broadcasting sport and esports to homes During COVID-19. International Journal of Sport Communication, 1-11, published online before print.

- Graeber, N. (2020, August 13). Schalkes “Miracle Run”: Vom letzten Platz in die Playoffs. Retrieved from https://www.volksstimme.de/e-sport/schalkes-miracle-run-vomletzten-platz-in-die-playoffs/1597323745000.

- Hallmann, K., & Giel, T. (2018). eSports – Competitive Sports or Recreational Activity? Sports Management Review, 21(1), 14-20.

- Handrahan, M. (2017, September 6). The fact is that most League of Legends teams lose money. Retrieved from https://www.gamesindustry.biz/articles/2017-09-06-the-fact-isthat-most-league-of-legends-teams-lose-money.

- Hebbel-Seeger, A. (2012). The relationship between real sports and digital adaptation in ESport Gaming. International Journal of Sports Marketing & Sponsorship, 13(2), 132–143.

- Heere, B. (2018). Embracing the sportification of society: Defining e-sports through a polymorphic view on sport. Sport Management Review, 21(1), 21-24.

- Hiltscher, D. (2005, June 12). Interview with SSV|roofman. Retrieved from https://www.readmore.de/articles/11407-interview-with-ssv-roofman.

- Hitt, K. (2020, August 25). Futbol Club Barcelona enters into esports collaboration with Tencent. Retrieved from https://esportsobserver.com/fc-barcelona-tencent-esports.

- Holden, J. T., Kaburakis, A., & Rodenberg, R. M. (2017a). The Future Is Now: Esports Policy Considerations and Potential Litigation. Journal of Legal Aspects of Sport, 27(1), 46–78.

- Holden, J. T., Rodenberg, R. M., & Kaburakis A. (2017b). Esports corruption: Gambling, doping, and global governance. Maryland Journal of International Law, 32(1), 236–273.

- Hutchins, B. (2008). Signs of Meta-Change in Second Modernity: The Growth of e-Sport and the World Cyber Games. New Media and Society, 10(6), 851–869.

- Jenny, S. E., Manning, R. D., Keiper, M. C., & Olrich, T. W. (2017). Virtual(ly) Athletes: Where eSports Fit Within the Definition of ‘Sport’. Quest, 69(1), 1–18.

- Johnson, S. (2020, October 19). Inside the explosive growth of college esports. Retrieved from https://www.redbull.com/us-en/theredbulletin/the-surge-of-college-esports.

- Jonasson, K., & Thiborg, J. (2010). Electronic sport and its impact on future sport. Sport in Society, 13(2), 287–299.

- Konami (2019, March 1). J.LEAGUE and KONAMI Team Up to Create eJ.LEAGUE Winning Eleven 2019 Season for All 40 J1 and J2 Clubs. Retrieved from https://www.konami.com/games/corporate/en/news/release/20190301.

- Lefebvre, F., Djaballah, M., & Chanavat, N. (2020). The deployment of professional football clubs’ eSports strategies: a dynamic capabilities approach. European Sport Management Quarterly, 1-19, published online before print.

- Liquipedia (n.d.) SSV Lehnitz. Retrieved from https://liquipedia.net/counterstrike/SSV_Lehnitz.

- Lombardo, J., & Broughton, D. (2017, June 5). Going gray: Sports TV viewers skew older. Retrieved fromhttps://www.sportsbusinessdaily.com/Journal/Issues/2017/06/05/Research-andRatings/Viewership-trends.aspx.

- Miah, A. (2017). Sport 2.0. Transforming Sports for a Digital World, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Mom, T. J., Fourné, S. P., & Jansen, J. J. (2015). Managers work experience, ambidexterity, and performance: The contingency role of the work context. Human Resource Management, 54(S1), 133–153.

- Nemerich, O. (2019, October 29). Interview mit Tim Reichert - “eSports wird weiter wachsen und seine Popularität wird zunehmen”. Retrieved from https://blog.osk.de/esportstim-reichert-s04.

- Oelschlägel, H. (2015, January 21). Turkish sports club Besiktas Istanbul acquires League of Legends team. Retrieved from https://www.eslgaming.com/news/turkish-sports-clubbesiktas-istanbul-acquires-league-legends-team-1230.

- Oezbey, A. (n.d.). FIFA 21 – BVB steigt mit grossem Content Creator in Esport ein. Retrieved from https://www.esports.com/de/fifa-21-bvb-dortmund-steigt-mit-grossem-contentcreator-in-den-esport-ein-121442.

- Pack, S. M., & Hedlund, D. P. (2020). Inclusion of electronic sports in the Olympic Games for the right (or wrong) reasons. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 12(3), 485-495.

- Parry, J. (2019). E-sports are not sports. Sport, Ethics and Philosophy, 13(1), 3-18.

- Paspalaris, C. (2016, October 4). Report: Timeline – Sports clubs in esports. Retrieved from https://esportsobserver.com/report-timeline-sports-clubs-esports.

- PSG (2017, October 5). We are withdrawing from League of Legends for now. Retrieved from https://psg-esports.com/we-are-withdrawing-from-league-of-legends-for-now.

- PSG (2018, April 19). PSG Esports on DOTA 2 with LGD Gaming. Retrieved from http://psgesports.com/psg-esports-on-dota-2-with-lgd-gaming.

- PSG (2020, June 18). Paris Saint-Germain partners with Talon eSports. Retrieved from https://en.psg.fr/teams/club/content/paris-saint-germain-partners-with-talon-esports.

- Rhein Neckar Löwen (2020, August 17). eSport Rhein-Neckar und Rhein-Neckar Löwen suchen Spieler für lokales League-of-Legends-Team. Retrieved from https://www.rheinneckar-loewen.de/esport-rhein-neckar-und-rhein-neckar-loewen-suchen-spieler-fuerlokales-league-of-legends-team-644471.

- Rietkirk, R. (2020, July 9). Newzoo adjusts esports forecast further in wake of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Retrieved from https://newzoo.com/insights/articles/esportsmarket-revenues-2020-2021-impact-of-covid-19-media-rights-sponsorships-tickets.

- Rosell Llorens, M. (2017). eSport Gaming: The Rise of a New Sports Practice. Sport, Ethics and Philosophy, 11(4), 464–476.

- Schmidt, S. L., & Holzmayer, F. (2018). FC Schalke 04 Esports. Decision making in a changing ecosystem. WHU Publishing Case Number CSM-0001, 1–21.

- Scholz, T. M. (2019). eSports is Business. Management in the World of Competitive Gaming. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Scholz, T. M. (2020). Afterword: An expert perspective on the future of esports. In D. P. Hedlund, G. Fried, & R. C. Smith III (Eds.). Esports Business Management, Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. In Press.

- Scholz, T. M. (forthcoming). The business model network of esports: The convergence of Overwatch. In Dal Yong J. (Eds). Global esports. Transformation of Cultural Perceptions of Competitive Gaming. New York: Bloomsbury.

- Scholz, T. M., & Stein, V. (2017). Going Beyond Ambidexterity in the Media Industry: eSports as Pioneer of Ultradexterity. International Journal of Gaming and Computer-Mediated Simulations, 9(2), 47–62.

- Seck, T. (2020a, September 10). Opinion: Why Guild Esports’ IPO Plans Should Raise Red Flags. Retrieved from https://esportsobserver.com/opinion-guild-esports-ipo-plans.

- Seck, T. (2020b, July 22). Q2 2020’s most impactful PC Games: Riot Games seizes esports world domination, continuing COVID-19 impact. Retrieved from https://esportsobserver.com/q2-2020-impact-index.

- Sieroka, F. (2020, July 16). VfB beendet eSports-Engagement. Retrieved from https://www.sport1.de/esports/fifa/2020/07/paukenschlag-vfb-stuttgart-beendetesports-engagement.

- Sims, A. (2020, April 27). Understanding The Esports Viewing Demographic. Retrieved from https://tnl.media/esportsnews/2020/4/22/understanding-the-esports-viewingdemographic.

- Superdata. (2015). eSports – The Market Brief 2015. New York: Superdata.

- Taylor, T. L. (2012). Raising the stakes: E-Sports and the professionalization of computer gaming. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- van den Bosch, J. (2020, August 10). Schalke 04 reach LEC playoffs after miracle run. Retrieved from https://www.esports.com/en/schalke-04-reach-lec-playoffs-after-miracle-run114131.

- Vermesse, M. (2003). #interview – SSV Lehnitz. Gamesports, 1, 6-7.

- von Au, C. (2017, February 14). Wenn Schalke gegen Paris Saint – Germain um den Aufstieg kämpft. Retrieved from https://www.sueddeutsche.de/digital/e-sport-wenn-schalkegegen-paris-saint-germain-um-den-aufstieg-kaempft-1.3378025.

- Witkowski, E. (2010). Probing the sportiness of eSports. In J. Christophers & T. M. Scholz (Eds.). eSports yearbook 2009 (pp. 53–56). Norderstedt, Germany: Books on Demand.

- Wochnik, S. (2015, January 21). Traditioneller Sportverein übernimmt E-Sport-Team. Retrieved from https://www.golem.de/news/tuerkei-traditioneller-sportverein-uebernimmt-esport-team-1501-111852.html.

- Wolf, J. (2019, April 11). Rockets agree to sell majority stake in Clutch Gaming to 76ers for $20 million. Retrieved from https://www.espn.com/esports/story/_/id/26490773/houstonrockets-agree-sell-majority-stake-clutch-gaming-philadelphia-76ers-20-million.